FORECAST

• If the Democratic Progressive Party wins the January 2016 presidential election, they are likely to revise or even relinquish Taiwan’s South China Sea claims.

• Washington will welcome any efforts to bring these claims in line with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

• Beijing will try to keep Taiwan from changing its decades-old policy of viewing the Chinese mainland and the South China Sea islands as one, indivisible territory.

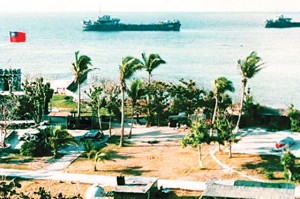

When China’s defeated Nationalists fled to Taiwan in 1949, they brought with them territorial claims to all of China, including a then unimportant group of islands in the South China Sea. Today, Taiwan claims sovereignty over a wide swathe of this sea defined by an “eleven-dashed line” nearly identical to China’s “nine-dashed line” delineating its own claims in the area. Taiwan’s military also maintains a presence on Taiping, the largest of the contested Spratly Islands, and on Pratas island in the northern South China Sea.

Ironically, the identical claims put forward by Beijing and Taipei have brought them into a sort of alignment, especially when contrasted with Washington’s vision for the region. The United States wants Taiwan to become a “responsible stakeholder” in the disputed waters by curtailing its claims and coming into accord with UN conventions. The United States sees Taiwan, along with nations such as Japan, as allies to counterbalance a rising China.

In the past altering island claims would have been anathema for a Taiwanese Kuomintang-controlled government that has steadfastly upheld the “One China Principle,” which maintains that mainland China and Taiwan are part of a single entity with competing governments. But Taiwan’s opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a strong chance of winning the January 2016 presidential election. With few ties to the mainland and little interest in maintaining the One China narrative, a DPP administration could conform with US wishes and, in doing so, alter the South China Sea strategy of both Taipei and Beijing.

Cold War legacies

In 1946, China’s ruling Nationalist government dispatched warships to claim the islands of the South China Sea as part of Guangdong Province. The naval group erected a stele on the tiny island of Itu Aba, which they renamed Taiping after the destroyer that claimed the island. A year later, the government published a map that included an eleven-dashed line encompassing most of the South China Sea. Today, this map still serves as the basis of the Republic of China’s claim. On paper, Taiwan maintains sovereignty over the entire area, although its military has scant capability to control much of the expansive sea. This brings Taipei in direct conflict with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which limits control of waters to 12 nautical miles from a nation’s shores plus a 200 nautical-mile exclusive economic zone.

The Communist-ruled People’s Republic of China inherited the eleven-dashed line when it formally took power from the Nationalists in 1949 and would go on to use it as the basis for its iconic nine-dashed line. For its part, when the Nationalist, or Kuomintang, government retreated to Taiwan it continued to claim to rule all of China. By 1950’s, however, Taipei possessed only the province of Taiwan, a few tiny garrison islands off the coast of China administered as parts of Fujian Province and Taiping Island in the South China Sea.

The Nationalist claims on territory actually controlled by the Communist government in Beijing were a source of concern for Taiwan’s treaty ally, the United States. The Nationalist government refused to accept the idea of two Chinas, instead staking its political survival on the fate of mostly indefensible sea islands it insisted on claiming along the coast and in the South China Sea. Washington feared being drawn into conventional or nuclear war over these disputed landmasses. It encouraged Taiwan to abandon its offshore holdings with limited success, only achieving the withdrawal of a few garrisons off the coast of Zhejiang province.

The Kuomintang government’s legitimacy rested on their claim to be the rightful rulers of China because they liberated it from Qing rule and Western imperialism. This in turn meant that China was single and united, not partitioned like the Koreas — such was the “One China” narrative. To maintain this, Taipei needed to maintain its island claims along the Chinese coast, including those inside the eleven-dashed line. Without these islands, the Republic of China was simply the historical province of Taiwan turned renegade.

Ironically, Beijing and Taipei agreed. Although having Taiwan claim sovereignty over the mainland was problematic, it would have been more troublesome had Taiwan formally seceded. The Communist government was content to allow Nationalist garrisons to maintain their positions to avoid completely severing the Republic of China’s geographic ties to the mainland.

One China or two?

But the once ironclad One China consensus within Taiwan is in the slow process of unraveling. With the Cold War waning in 1987, Taiwanese President Chiang Ching-kuo declared an end to 38 years of martial law. For the first time, parties besides the ruling Kuomintang became legal. The most important of these was the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The DPP differed from the Kuomintang in that its constituents were primarily Taiwanese who had lived on the island before the arrival of the Nationalist mainland exiles in 1949. This population had little sentimental attachment to the mainland or to the idea of greater China.

Two-party rule became a reality with the election of President Chen Shui-bian from the Democratic Progressive Party. Chen was native born, not an exile, and widely perceived to be in favor of declaring official independence from China — a red line for Beijing. His eight-year presidency strained relations with China. Concerned that the administration would declare independence, China passed the anti-secession law in 2005 and continued to build up its military to outmatch that of Taiwan. Washington was equally concerned by the destabilizing potential of the DPP government, and Taiwan’s relationship with the United States suffered.

Tensions decreased in 2008 when the establishment Kuomintang returned to power under President Ma Ying-jeou. Ma’s presidency was built on stabilizing relations across the Taiwan Strait. Under his rule, Taipei has avoided making political provocations and built economic ties with the mainland. He sold this program as a way to reverse the economic stagnation that began under the previous administration.

Unfortunately for the Kuomintang, Ma’s program failed to deliver the strong growth he had promised. Worse still, many Taiwanese believed Ma’s economic policies were bringing Taiwan too far into China’s orbit. This manifested in protests against the Cross Strait Services Trade Agreement, which began in March 2014 and lasted months, culminating in demonstrators occupying Taiwan’s legislative building. Afterward, presidential and Kuomintang approval ratings fell to record lows.

With the Kuomintang weak, the DPP made gains during the November 2014 local elections. The number of Kuomintang-controlled cities and counties dropped from 15 to six, and the party lost traditional strongholds such as Taipei. Cross-strait policy has been only one of several factors behind DPP’s success in the latest round of elections and was in fact a liability as late as 2012. This seems to have reversed, and now DPP’s policies resonate with voters leading up to the 2016 presidential elections. The party’s candidate, Tsai Ing-wen, has gained a great deal more popularity than her Kuomintang rival, Hung Hsiu-chu. Much of this is due to Hung’s push for “One China, Same Interpretation,” a policy that Hung claimed to be about pushing Beijing to recognize the Republic of China government, but was seen by many Taiwanese as evidence that Hung wanted reunification.

Sea change

Regardless of the outcome of the upcoming elections, ideological commitment to the idea of One China is clearly diminishing. In the days of the Kuomintang party state, the party’s stance was Taiwan’s stance. Now the DPP looks likely to take power again – or at least give the Kuomintang a run for its money. Nonetheless, Taipei’s remote outposts in the South China Sea are still a useful relic for resource exploration and one of the few possessions that prevent it from simply being limited to the main island. Beijing hopes that this will prompt Taiwan to maintain the status quo by neither renouncing nor amending its claim.

Only this will keep the two powers on the same page, at least on this limited issue.

Beijing worries that a DPP administration will be much less committed to preserving the One China Principle. This is with good reason: DPP policymakers have called for outright abandonment of Taiwan’s South China Sea claims in the past. While the Taiwan-held offshore islands of Kinmen and Matsu off the coast of China’s Fujian province have permanent civilian populations that would protest if the islands’ legal status were altered, Taiping has no civilian constituency. Furthermore, many Taiwanese perceive Taiping to be of marginal economic value, with its few mineral resources and its distance from Taiwan, which makes it more or less inaccessible to fishermen.

A less dramatic option for a prospective DPP government would be to reinterpret or relinquish the eleven-dashed line instead of abandoning the islands of Taiping and Pratas outright. Even this would cause problems for Beijing. Because the Republic of China originated both Taiwan’s claim and that of the mainland, Taiwan reneging would give ammunition to rival claimant countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines. China would also no longer be able count on implicit backing if Taiwan drops its shared claim. And in the near term, Beijing may face supply problems for its installations in the Spratly Islands, which receive at least part of their water supply from the Taiwanese forces on Taiping.

Without a common purpose, Taiwan would have no incentive to continue sending water.

Under US President Barack Obama and renewed focus on the Asia-Pacific, US policymakers have been anxious to push Taiwan to bring its South China Sea claims in line with international law. Washington sees this as a way of transforming Taiwan into a “responsible stakeholder,” meaning one that upholds UN standards instead of a sweeping claim identical to that of Beijing. The US push makes a DPP relinquishment even more likely: Chen’s presidency suffered from poor US ties, and this move could be beneficial for Taiwan and the United States alike. Taipei could even barter the resulting goodwill to secure additional US assistance, including political aid to join the second round of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, backing to take more of a role in international organizations or simply more military assistance.

Ultimately, a victory for the DPP is not guaranteed – elections are difficult to forecast. The issue at stake – the nature of Taiwan as the true Chinese government or an independent island – will continue to be fought out in the coming years, with the South China Sea claims being one of the first likely casualties.

--© 2015, STRATFOR GLOBAL INTELLIGENCE